In a pre-Covid-19 world, depression and anxiety were estimated to cost the global economy more than US $ 1 trillion per year1 in lost productivity. From recent discussions with companies on workplace wellbeing we notice a recurring theme: if mental health was emerging as a key focus area, it now most certainly is a priority for employers.

Diet and mental health at the workplace in a Covid-19 era

What is not often spoken about- in the nutrition community, or in the business world- is the link between nutrition and mental health. Emerging evidence from the literature shows that healthy diets can support mental health outcomes, and vice-versa. This relationship can be broken down into the following categories:

a- Emotions, food, and mood

What we eat, or on the contrary do not eat, can affect our mood in the short term. Not eating regularly can lead individuals to experience low moods due to blood sugar fluctuations, particularly among people living with diabetes2. Conversely, our emotions can induce specific eating behaviours. Whilst intense bursts of emotion can suppress appetite, lower intensity emotions (such as chronic stress) are linked to increased intake of sweet and high-in-fat foods3. An effect which many can relate to in the wake of Covid-19.

b- Long term links between diet and mental health

Both obesity and depression are of concern to employers and public health specialists alike4,5. An important study6 examining pooled data from longitudinal studies in Europe and the USA found that:

- On one hand, people with obesity at the start of the studies had a 55% increased risk of developing depression later in life.

- On the other hand, the study found that depressed people at baseline had a 58% increased risk of becoming obese later in life.

This is consistent with the results of studies highlighting the correlation between consuming a diet high in intensively processed foodsa and psychiatric symptoms7,8. It also shows how eating is influenced by emotional state, and can translate into weight gain over time3.

On the flip side, recent randomized control trials – the gold standard of scientific research- found promising results by using dietary interventionsb to support depression treatment9,10. These results are backed by population-level studies suggesting that a diet high in fruit and vegetables is correlated with lower odds of developing depression11,12.

“Due to the scale of the burden of mental, neurological and substance-use disorders and the universality of food as a modifiable risk factor, even small improvements in the nutritional environment may translate to large gains in mental health and wellbeing at a population level.” 13

c- Food insecurity and mental health

Beyond the biological impact that food can have on our bodies, there is also a social element to food that can’t be neglected. A 2019 study conducted across 149 countries found that food insecurity was consistently associated with poorer individual mental health14. Anxiety around acquiring food in socially acceptable ways, as well as feelings of shame, seem to be driving this association. Pre-Covid-19, 820 million people found themselves in a position of food insecurity. With the current economic predictions, this number will likely see a significant increase over the next few months, making this issue all the more pressing15.

What is a healthy diet?

A healthy diet is one that meets the nutrient and energy requirements of an individual, promoting health and protecting from disease. This includes consuming more fruit and vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and protein- rich foods, but less added sugars, fats and salt.

How can employers make the most of the synergies between nutrition and mental health?

The evidence on the synergies between mental health and nutrition is compelling, and employers have a role to play given that the average adult spends around one-third of their time at work.

Not only are worker wellbeing programmes the right thing to do, but they also make business sense. The WHO estimates that for every US $ 1 invested in mental health support, there is a reported return of US $ 4 in productivity and improved health16. Similarly, employers report benefits such as reduced absenteeism, lowered rates of mistakes, enhanced productivity, and reduced medical costs from implementing workforce nutrition programmes17.

What is a workforce nutrition programme?

Workforce nutrition programmes are a set of interventions that work through the existing structures of the workplace to create improved access to – and demand for – safe and nutritious food. The aims of these programmes is to change employees’ behaviours around food consumption, and improve their health and wellbeing.

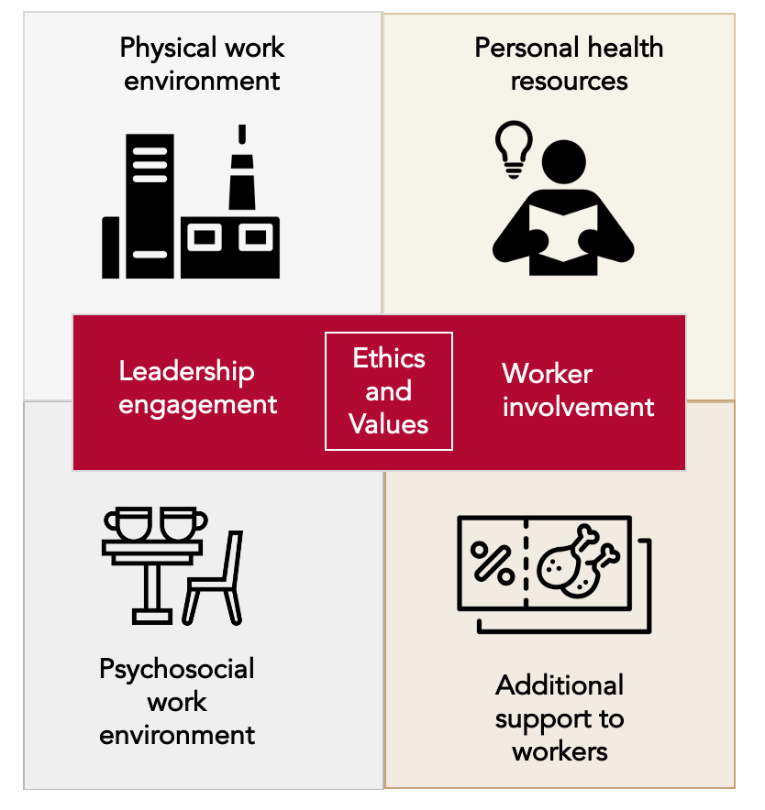

Figure 1: Healthy Workplaces Framework. Adapted from the WHO ‘Five Keys to Healthy Workplaces’, 2017.

Within the Healthy Workplaces framework and based on our review of the evidence for workforce nutrition programmes we suggest a few concrete practical steps employers can take to improve their employees nutritional habits, and with this possibly contribute to supporting mental health outcomes:

Personal health resources:

- Offer nutrition counselling alongside mental health support services

- Share accessible information with employees to make them aware of the link between mental health and nutrition

Physical work environment:

- Improve the food offerings at the workplace to promote healthier snack or meal alternatives which are rich in whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes

- Display or serve food in a way that encourages healthier choices with strategies including calorie labelling, recommended portion sizes, and product placement

Psychosocial work environment:

- Encourage employees to take regular eating breaks away from their workstation to be mindful of their eating habits

- Set up a dedicated eating space that encourages socialisation during eating breaks

- Include the voices of workers in designing programmes and ensure consistent engagement from leadership

Additional support to workers

- Support vulnerable employees and their families with a short-term buffer against nutritional insecurity through vouchers or subsidized / free food baskets

- Consider extending nutrition and mental health services and/or materials to the families of workers

The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted just how intertwined food and mental health are. Many of us have read the evidence: healthy diets support good immune system function and are thus important in maintaining physical health. In this blog, we show how healthy diets also support mental health and vice-versa, which has never been more important. For employers interested in building more holistic worker health programmes, finding synergies between nutrition and mental health programmes is key to a more resilient workforce.

GAIN and The Consumer Good Forum have launched a Workforce Nutrition Alliance to support employers and catalyse action on improving Workforce Nutrition.

Geneviève Stone

Junior Associate

Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN)

Bärbel Weiligmann

Senior Advisor – Better nutrition

Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN)

For further information about workforce nutrition programmes, please visit: https://www.gainhealth.org/impact/programmes/workforce-nutrition.

For any queries contact us at: [email protected].

References

a. These are foods that may have high levels of salt, sweetener, and fats, as well as artificial additives that increase palatability and promote shelf life.

Such dietary interventions included the use of the Mediterranean diet which is characterised by a high consumption of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and healthy fats.

b. Such dietary interventions included the use of the Mediterranean diet which is characterised by a high consumption of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and healthy fats.

1. United Nations. Policy Brief: COVID-19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health. 1–17 https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/un_policy_brief-covid_and_mental_health_final.pdf (2020).

2. Penckofer, S. et al. Does glycemic variability impact mood and quality of life? Diabetes Technol. Ther. 14, 303–310 (2012).

3. Macht, M. How emotions affect eating: A five-way model. Appetite 50, 1–11 (2008).

4. NCD Alliance. Realising the potential of workplaces to prevent and control NCDs: How public policy can encourage businesses and governments to work together to address NCDs through the workplace. (2016).

5. Business Group on Health. Addressing Mental Health from a Global and Local Perspective: A Guide for Employers. (2020).

6. Luppino, F. S. et al. Overweight, Obesity, and Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67, 220–229 (2010).

7. Jacka, F. N., Cherbuin, N., Anstey, K. J. & Butterworth, P. Dietary Patterns and Depressive Symptoms over Time: Examining the Relationships with Socioeconomic Position, Health Behaviours and Cardiovascular Risk. PLoS One 9, (2014).

8. Sousa, K. T. de, Marques, E. S., Levy, R. B. & Azeredo, C. M. Consumo alimentario y depresión entre adultos brasileños: resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de Salud, 2013. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 36, (2020).

9. Jacka, F. N. et al. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC Medicine 15, 23 (2017).

10. Parletta, N. et al. A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: A randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutr Neurosci 22, 474–487 (2019).

11. Saghafian, F. et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of depression: accumulative evidence from an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. British Journal of Nutrition 119, 1087–1101 (2018).

12. Baharzadeh, E. et al. Fruits and vegetables intake and its subgroups are related to depression: a cross-sectional study from a developing country. Ann Gen Psychiatry 17, 46 (2018).

13. Owen, L. & Corfe, B. The role of diet and nutrition on mental health and wellbeing. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 76, 425–426 (2017).

14. Jones, A. D. Food Insecurity and Mental Health Status: A Global Analysis of 149 Countries. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 53, 264–273 (2017).

15. United Nations. Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/sg_policy_brief_on_covid_impact_on_food_security.pdf (2020).

16. WHO. Mental health in the workplace: Information sheet. (2019).

17. Stone, G. & Nyhus Dhillon, C. The evidence for workforce nutrition programmes. in The Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (2019).